In the landscape of Canadian politics, the New Democratic Party (NDP) has long stood as a voice for workers, the marginalized, and those left behind by the profit-driven politics of the Liberal-Conservative establishment. But like any political force, the NDP’s roots, evolution, and relevance are worth examining—especially for those of us in the labour movement.

The Birth of a Movement

The NDP wasn’t created in a boardroom or dreamt up by pollsters. It was born out of worker struggle and grassroots organizing. In 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression, a coalition of farmers, trade unionists, and socialists came together to form the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Its founding document, the Regina Manifesto, was nothing short of radical for its time. It called for the eradication of capitalism and the establishment of a democratic socialist economy where human needs came before corporate profits.

Tommy Douglas, a former Baptist preacher and CCF Premier of Saskatchewan, became the face of this growing movement. He introduced universal healthcare in his province, laying the groundwork for the national Medicare system we value today. Under Douglas, the CCF proved that social democracy wasn’t just rhetoric—it was a model for governance that prioritized people over profits.

From CCF to NDP: Labour Enters the Arena

By the late 1950s, the CCF faced declining support and internal divisions. Meanwhile, the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) was looking for a stronger political partner to represent workers’ interests. In 1961, the two forces merged to form the New Democratic Party. The NDP’s formation was more than a rebrand—it was a historic alliance between organized labour and political activism.

The NDP’s founding principles remained rooted in social and economic justice, but with labour’s institutional support, it gained a solid base of working-class support. And while it never formed federal government, it consistently influenced national policy—particularly in areas like Medicare, pensions, workers’ rights, and environmental protections.

Pushing the Liberals Left—Or Propping Them Up?

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the NDP played the role of conscience in Parliament. In 1972, under David Lewis, the party held the balance of power in a minority Liberal government and used that leverage to secure significant investments in public housing, pensions, and job creation. Lewis popularized the term “corporate welfare bums” to criticize the billions handed to big business while workers struggled to get by.

But the line between strategic influence and co-dependence with the Liberals has always been thin. The NDP has often found itself supporting Liberal budgets or social policies in exchange for incremental wins. For the labour movement, this raises a recurring question: is the NDP pushing the Liberals to the left, or enabling them to avoid governing boldly?

Provincial Power and Policy Wins

While federal power remained elusive, the NDP found success provincially. In addition to Douglas in Saskatchewan, the party later formed government in British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Alberta. These governments introduced progressive tax reforms, labour protections, social housing initiatives, and environmental regulations. But they also faced backlash when governing in tough economic times, particularly during the 1990s.

The Bob Rae government in Ontario (1990–1995) is often cited—fairly or not—as a cautionary tale. Elected on a wave of hope, Rae’s government was quickly forced to confront a brutal recession and ballooning deficits. Controversial policies like the “Social Contract” alienated many public sector workers and left scars within the labour movement that linger to this day.

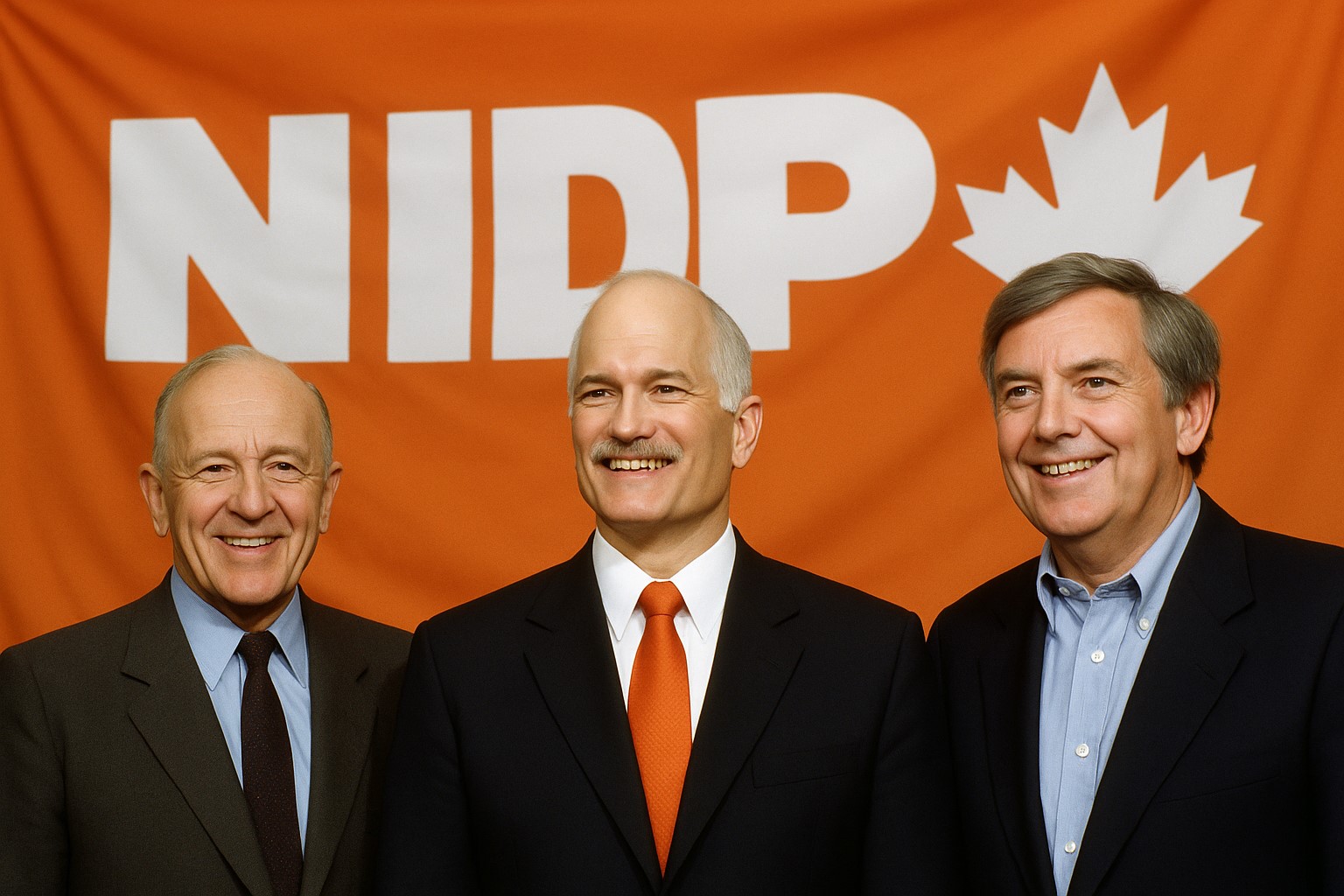

Jack Layton and the Orange Surge

In 2003, Jack Layton, a Toronto city councillor and lifelong advocate for homelessness, public health, and environmental justice, became federal NDP leader. Layton brought charisma, optimism, and a renewed sense of mission to the party. He positioned the NDP as a viable alternative to the Liberals—not just a protest party.

In the 2011 federal election, Layton led the NDP to its best showing in history, winning 103 seats and becoming the Official Opposition. This “Orange Surge” was driven largely by a breakthrough in Quebec, where voters rejected the Bloc Québécois and rallied behind Layton’s positive message.

Tragically, Layton passed away shortly after the election, cutting short a transformative moment for the party.

Recent Years and Lingering Questions

Since 2011, the NDP has struggled to reclaim that momentum. Under Thomas Mulcair, the party moved toward the political centre, hoping to appear “ready to govern.” But this shift alienated some of the base and resulted in a disappointing 2015 election, where the Liberals under Justin Trudeau absorbed much of the progressive vote.

Jagmeet Singh, elected leader in 2017, brought a new face and fresh energy to the party. Singh has spoken passionately on racial justice, inequality, and workers’ rights. Under his leadership, the NDP has won concessions from the Liberal minority government on dental care, pharmacare, and housing.

But critics within the labour movement question whether the party has lost its radical edge. While Singh’s NDP champions many working-class issues, its willingness to prop up Liberal governments without demanding transformational change raises concerns about its long-term vision and independence.

A Party at the Crossroads

For those of us in unions and grassroots movements, the NDP has always been more than a party—it has been a vehicle for our collective hopes. But we must ask ourselves: is it still that vehicle?

The NDP’s history is rich with moments of courage and achievement. But history alone won’t win the future. If the NDP wants to remain the political home of workers, it must return to its roots—bold, unapologetic, and rooted in solidarity.

Because while capitalism adapts, inequality deepens, and public services are eroded, we don’t need cautious management. We need transformative leadership. The kind that built Medicare, challenged corporate power, and dared to dream of a better Canada.