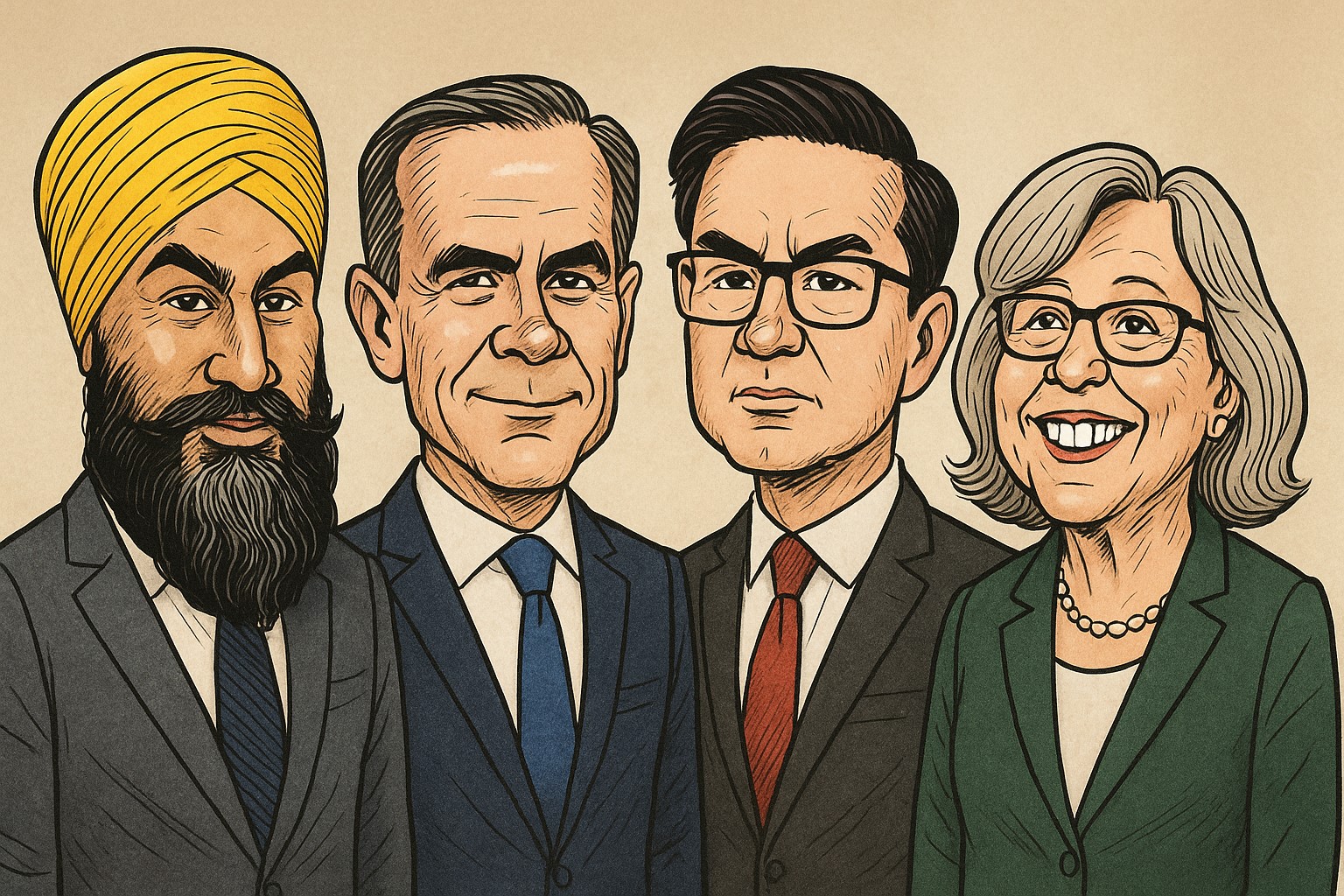

There was a time when Canada’s political parties spanned a recognizable spectrum: Liberals to the centre-left, Conservatives to the centre-right, and the NDP anchoring the left. But in recent years, that spectrum has lurched rightward. Today, with a Carney-led Liberal government in Ottawa and a hard-right Conservative opposition under Pierre Poilievre, many workers and union members are wondering—who, exactly, is still standing with labour?

The Liberals Under Carney: Calm, Corporate, and Centre-Right

Mark Carney’s rise to power was pitched as a return to competence. His background—Governor of the Bank of Canada, Governor of the Bank of England, and a darling of international finance—reassured elites and steadied Liberal ranks after years of turbulence and scandal under Trudeau. For business leaders, he was a safe pair of hands. For union members? The jury is very much out.

Since taking office, Prime Minister Carney has embraced a tone of technocratic moderation. The language is polished. The policies, less so. While the Liberals still speak of progressive values—climate action, inclusion, economic resilience—their decisions have largely catered to the private sector and fiscal conservatives.

Workers were promised reform on issues like Employment Insurance, gig economy protections, and housing affordability. But Carney’s government has prioritized economic stability over structural change, opting for market-based solutions and public-private partnerships. For organized labour, that means the status quo—precarity for many, corporate leeway for the few.

Despite friendly meetings and photo ops, the federal government has yet to deliver meaningful gains for unions. And while anti-scab legislation finally passed, it was long overdue and only came after years of pressure from labour.

Conservatives Dig In on the Right

If the Liberals have shifted to the right of centre, the Conservatives under Pierre Poilievre have charged further. His messaging—anti-union, anti-public service, anti-regulation—has gained traction with voters frustrated by economic stagnation, but it offers little for working Canadians.

Poilievre’s party has repeatedly blamed federal workers for inflation, attacked union wage gains as excessive, and floated the idea of “right-to-work” style laws that would severely undermine union power. For public sector workers, in particular, the Conservative vision is one of rollbacks, austerity, and privatization.

It’s a brand of politics built not on solving inequality, but on exploiting frustration—pointing fingers at those with modest job security rather than challenging those hoarding extreme wealth.

The NDP: Too Quiet for a Time Like This

Amid this rightward drift, the New Democrats should, in theory, be seizing the moment. But after years of supporting Liberal governments through supply-and-confidence agreements, the NDP finds itself in an awkward position—still the most labour-friendly party in Parliament, but struggling to assert its independence or galvanize mass worker support.

Under Jagmeet Singh, the NDP has offered solid proposals—universal pharmacare, anti-scab legislation, rent relief—but their impact has been dulled by cautious messaging and a lack of visibility outside major election cycles. For many union activists, the party has become too quiet, too careful, and too accommodating.

The challenge now is whether the NDP can break out of this holding pattern and become the bold, unapologetic voice that working-class Canadians desperately need.

What Carney’s Government Signals for Labour

For the labour movement, the Carney government is not an ally, nor an overt adversary—it is a polished middle manager of a status quo that no longer works for working people. Under the surface of calm fiscal leadership is a clear reluctance to confront inequality, corporate power, or the erosion of public services.

The risk for unions is complacency. A Liberal government that “sounds” progressive while governing as centre-right can lull people into inaction. But Carney’s policies so far show no real intention to strengthen union rights, expand the public sector, or challenge the structural forces driving economic insecurity.

The window for polite negotiation is closing. If organized labour doesn’t demand more—louder, faster, and more forcefully—we risk being left behind altogether.

What About the Alternatives? A Look Beyond the Mainstream

If neither of the major parties is delivering for workers, and the NDP is struggling to assert itself, where else can labour turn?

The Greens: Progressive, but Peripheral

The Green Party of Canada consistently polls on the political left, especially on environmental and social justice issues. Their platform often includes strong language on universal basic income, democratic reform, and climate justice. They support union rights in principle, but have historically lacked deep roots in the labour movement.

With minimal union affiliations, limited infrastructure, and few elected MPs, the Greens remain on the fringes. For some activists, the Greens are attractive in theory—but their electoral ceiling and lack of working-class engagement leave them more symbolic than strategic.

The Libertarians: A Non-Starter for Labour

While they may attract attention for their rhetoric on freedom and personal rights, Libertarian politics are fundamentally anti-labour. Their ideology opposes collective bargaining, public services, and workplace regulations. In their world, unions are interference, not empowerment. For the labour movement, this is not an option—it’s the opposition in disguise.

Socialist and Marxist Parties: Theoretical But Fragmented

Canada has long had small socialist and Marxist political parties—the Communist Party, the Socialist Action group, and others. Their platforms align closely with labour’s core values: worker control, public ownership, wealth redistribution, and anti-capitalist reform.

But these parties have never cracked the mainstream. Electoral barriers, limited media coverage, and internal fragmentation have kept them on the sidelines. Still, their presence serves as a moral compass for the broader left—reminding us what unfiltered, unapologetic worker-first politics could look like.

A New Party? A Labour Party?

Some have floated the idea of creating a new political party—one led by unions, working-class organizers, and social movements. A modern Canadian Labour Party, independent from existing structures, modeled on the early roots of the NDP or Britain’s Labour movement.

It’s an enticing idea, especially for younger workers and activists disillusioned with the current parties. But it comes with immense challenges: resources, organizing capacity, legal hurdles, and the risk of vote-splitting. Still, with union density declining and political influence waning, it may be a conversation worth having.

Or Reinvent the NDP?

Despite its shortcomings, the NDP remains the only party with institutional labour ties, a national presence, and potential for meaningful transformation. Many in the union movement believe the NDP doesn’t need to be abandoned—it needs to be reclaimed.

That would mean pushing the party to:

- End complacency with Liberal governments

- Empower more working-class and union candidates

- Embrace bolder, movement-driven policy (not just electoral strategy)

- Invest in ground-level organizing—not just advertising

- Hold corporate power to account with clarity and consistency

In other words: the NDP must choose—will it be the party of workers, or the party of managing decline?

Time for Labour to Lead

Canada’s political spectrum is off balance. The right is emboldened. The centre has shifted. And the left—what’s left of it—is disoriented.

But the labour movement has never waited for permission. When workers organized unions, demanded the weekend, built Medicare, and fought back against privatization, it wasn’t because political parties led the way. It was because we did.

We’re here again.

Whether through the NDP, a reimagined party, or a renewed mass movement, labour must once again be the driver—not the passenger—of political change. We don’t need to choose between silence and surrender. We can fight. We can organize. And we can win.

But only if we start leading.